Southern Legitimacy Statement: I frequently think about how the South and it’s defining characteristics, good and bad, exist in other cultures and, more recently, have reflected on that in my writing while carefully cultivating timely opportunities for drinking Coke and eating BBQ.

The Butteri and The Batture

There are aspects of Italian life, their cultural zeitgeist, time markers through antiquity that seem as if they will last forever and which serve to burnish our own indelible ideals and memories. The values woven into this type of existence are as enduring as the art and antiquities of Italy, its medieval towns, and the food and traditions that are infused in the Italian soul. La dolce vita.

Remember that Italy did not become a sovereign state until 1861. It was preceded by centuries of an ancient past, individual kingdoms under Rome’s province, with poets and artisans immortalizing Emperors whose powers exponentially extended the boundaries and influence of the empire complicit with the spiritual reach of the church and the Popes. There were, of course, periods of corruption and decline over the centuries of the empire’s rule. Later, as Italy began to modernize after unification, it suffered a repressive period of fascism lasting from 1922 to 1943.

Irrepressibly, the people endured and keep their society’s connective traditions alive. They remained close to the land, extended the long practiced craftsmanships of leather-working, weaving cloth, being exceptional vintners, pressing olives from centuries-old trees, and working horses in the Maremma region.

The mounted herdsmens, the butteri, who are predominantly of the marshy Maremma region of Tuscany, have a culture that goes back to Etruscan times and the development of agriculture but are now fighting to survive the erosive effects of relentless modernity. They are aging cowboys maybe a generation or two from extinction – resigned to squeezing out only an inevitable last dram of precious time from the passing millenniums’ cask of finely aged wine. The gene pool of the original Maremma horses, cattle and men is disappearing like the soft but quickly fading light at day’s end.

New Orleans has its own, admittedly briefer, colorful history, too. It was inhabited by Native Americans for approximately 1300 years with archaeological dating to settlements going back to approximately 400 A.D. French fur trappers and traders arrived in the late 17th century and built on a trading foundation laid out originally by the Native Americans. The City of New Orleans came into existence in 1718, founded primarily by the French, but attracting a widely diverse population as it grew into a major port and a significant Southern cultural center over time.

Agriculture here, too, played a significant role in developing the rich flood plain of the Mississippi River and creating fortunes from sugar cane and cotton savagely built on the backs of slave labor. Drainage projects opened more land for agriculture, but also created new land for development and expansion of the city – much like was experienced in the Maremma region in Italy.

With the 20th century, New Orleans, not withstanding its sometimes fractional diversity and the inherent genetic code of the city’s founding days’ wildness, came a time of literary and artistic ascendency. A more sophisticated drainage system in the city and reinforced levees created a fragile sense of security, that amongst other influences such as ease of travel and increasing personal middle class wealth, brought a sweeping economic surge of tourism – not entirely changing the city, but slowing distancing itself, if you cared to notice, from its surrounding but shrinking natural environs.

The food culture in greater New Orleans has, for me, a recognizable correlation to that of Italy in its depth of tradition, simple but innovative flavors built on freshness of locally sourced ingredients, and a joy in the familial gathering of family and friends.

While a party atmosphere permeates and largely defines the outsider’s image of the city, it still maintains a whisper of it’s underlying gentility mixed with pockets of a renewed vibrancy in the districts ravaged by Katrina in 2005 but with isolated areas still impoverished and abandoned in ways that may never heal or scar over.

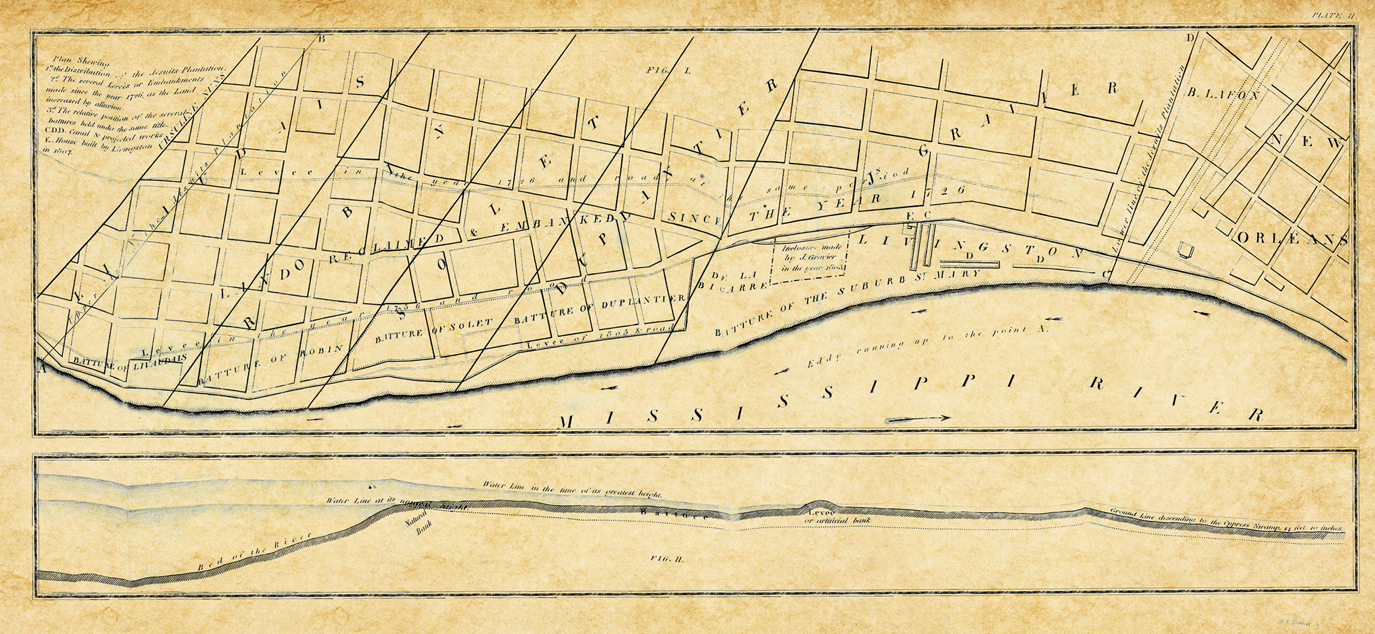

A historically interesting geographic aspect of New Orleans’ development is the batture, alluvial land created by the accretion of soil that is deposited between the low tide river and the levee and built up substantially in times of heavy flooding. Over time, it becomes valuable land rich for development. From the founding of the City of New Orleans on, there has controversy as the batture, while originally treated as public land, also helped to expand the city’s land mass. Thankfully, it has retained the treasured public function of being a place of refuge, a place to simply stroll and enjoy the cooling breezes from the river, to reconnect with the ancestral origins of the native settlements, to watch the river flow by, to observe wildlife in their natural habitat, and to catch glimpses of eagles returning to their nests as the golden light of the sun fades into the night.

In the most historically significant places in our world, with their vestiges of medieval architecture and binding customs, and also in those lesser known places that are still environmentally protected by their isolation, where gargoyles still stand sentry, wild horses still roam through a dream-like landscape herding the still wild Maremmana breed of cattle, and where the river and land share common ground, there is a sense that the old ways, the enduring traditions, the familial closeness, and a symbiotic attachment to the land stand as stark and presciently telltale markers unveiling our future.