Southern Legitimacy Statement: I was born in Richmond, Virginia and raised on a thoroughbred race horse farm in nearby Ashland. My upbringing pulses in my veins: I have been blessed by both earth and animal.

Shooting Holes in Signs

Grandpa’s .22 bolt action, plus a pocketful of plinking bullets.

Dependable, a history of varmint hunting and honor

hand-rubbed into its fine maple stock. Of course

the local editorials and chock-a-block letters to the editor

rage about guns, rant over reckless and illegal shooting,

the general voice seethes over taxpayer money

bleeding out for sign replacements. But I’m not one of those

“Bubba Sports” enthusiasts doing the public dirty

by four-wheeling sweet summer hiking trails, grinding out

deep rutting fun, creating black mud depressions;

I don’t wintertime thumb my nose at Fish & Game

by skimming a snowmobile over open water while pulling

one seriously beered-up water skier behind me.

That’s somebody else clouding the issue: my pastime

is imbued with gunpowder-grain and sulphurous purpose.

Staying on the right side of the road, I cruise, then nighttime park,

choosing my targets carefully. I know Deke Smitty beats his wife—

so his Used Cars sign needs to bleed enamel and rust while bruising

just a little. The proposed development 24 X 12 billboard

along the frontage of McMillan’s bank-taken farm

might not get too many plot-takers if potential buyers feel

there’s a nest of rankled hillbilly-rattlers hiding in the bushes

bearing fanged weapons. The XXX Shop peddling smut

needs an angry face hollow-point punched in its

neon sleeze-metal girly-form as a brazen reminder that some of us

raise daughters and we surely don’t approve.

I revere stop signs, refuse to desecrate pedestrian instructions

and the yellow announcements of deer crossings.

Before blowing out my breath and squeezing the trigger

I give due consideration to where that bullet will finally land

in the far distance. Don’t much like signs in the first place,

but being responsible is important when you send a message

to anyone traipsing or selfish-ing round about the community: whole

and wholesome must be preserved with public displays and the threat of

punctures, our rough and ragged-edged way of letting the sun shine through.

***

No Pity For Poor Boys

In the ramshackle night

they talk between windows

with tin cans united by string,

blink flashlight coded messages of tomorrow doings

into the gloom long after lights out.

In the heat shadows of day a long hardwood stick

becomes a gun, or a sword, the oils of the hand smoothing

its martial surface, and imagined defense against

the advancing army is bolstered by notorious

friends, an adopted pound dog, by green leaves and the air.

In time, cans and bottles become

faceless targets for rocks chosen according to

shape and heft, aluminum denting and

glass dust bursting under hours of practice,

chisel-pointed rainbows against the sun.

In summer, the steep hillside becomes a raceway

for cardboard boxes sliding the green, then later in winter

they ride trays stolen from fast food joints, or ride

an abandoned car hood seven shooshers strong

screaming against icy gravity. They grow, bold.

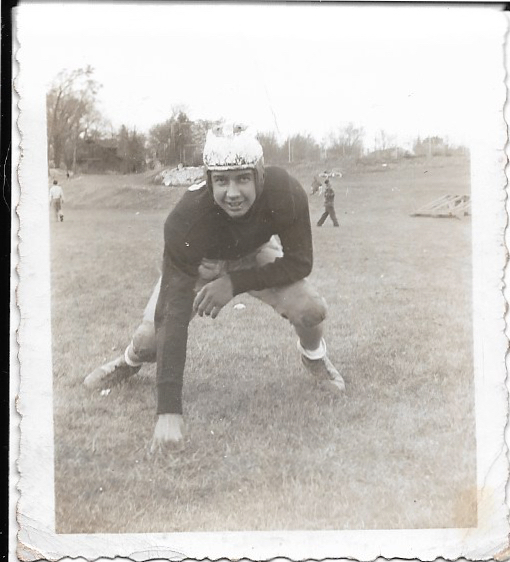

In the passage of days the poor boys wrestle, box, run

when they break things, tough and fast and careless

with the law. Worried mothers do not know where they are

half the time—but they are happily bruised and fine, they own escape

routes, both real and the just maybe possible. Danger is their friend.

And if you shake your head at their prospects,

then you’ve never seen the face of a young woman

skinny dipping at midnight, embracing a poor boy’s

warmth against the cold racing water, moonlight

filling her smile against the pull dividing around them.

***

North End of Town

The supposedly seedy end, an old tottering

beat trailer/tar paper shack extremity

of human habitation with barely-there ditches

sluicing rainwater and beer cans through poison sumac

bittersweet and jointweed whenever thunderheads

crack, the deluge curling toward a shanty-land

with chickens scrabbling across the roads crazed by a hunger

for brown grasshoppers. The scary part of town

that wild rich boys dare in the nighttime

recklessly aiming their gleaming trucks and sports cars

into streetlightless blind-curves while attempting to lose

pursuing cops, turning their headlights off and picking

a crooked fork in those dangerous parts where wise folk

don’t go after dark. The unfortunate extension of fissured

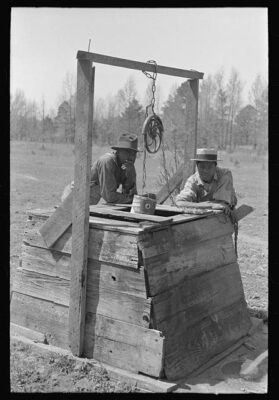

grass-overgrown tarmac—home to kids who skew

the high school’s dropout numbers, ancestral birthplace

to hard-ass parents hanging on to each other

and their seasonal second shift jobs at the cannery,

bridge-fishing the river for a no-cost pan-fry supper,

picking the free room clothing bin at the dump

on weekends. Here’s what the hellion and high-mighty

don’t know: everyone residing out where the town line fades

lives surrounded by lilacs, tough light-seeking shoots

all descended from a single bush someone smiled over

and shared around with all the others scratching

out a life a hundred years ago. In every single struggle

of country yard there are light purple olfactory beacons

blooming with spring ambrosia, a community

of cascading flowers, honey and bumble bees, Monarch

and Viceroy butterflies bouncing along with

ruby-throated hummingbirds flitting their aerial pirouettes

in annual duty to pollinating a golden wide world

for its own good. When spring descends on the north end of town,

just like it does everywhere, fine people should choose

daylight and cruise out that way, breathe in

and live in that momentary sweetness where a gratifying ease

has taken root, where the cost of neighbor

waving to neighbor is as precious

as a perfumed cutting, lovingly brought inside,

prospering in a mason jar.