SOUTHERN LEGITIMACY: I was born in Savannah and lived all my life in Georgia until I graduated from the University of Georgia. My mother was born in Paducah, Kentucky, and her mother in a village in west Tennessee too small to have a name. Her father, Orlando Payne, owned slaves, fought with the Confederacy, and remained unreconstructed through the beginning of the Twentieth Century. For balance, Orlando Payne was first cousin to Cassius Marcellus Clay, the Kentucky abolitionist. I tend to side with Mr. Clay’s politics, but I still believe in courtesy and grits.

MY HOUSE HAS PROBABLY FALLEN IN BY NOW

but I doubt the beach is quite yet gone.

I hear the old Tybee road’s still okay,

if you drive slow.

They got rid of those rusted “Erector Set” bridges,

no more waiting while some dumb dinky

boat with a high mast

makes the bridge turn sideways

on a stack of pulleys and gears

I would’ve loved to’ve fiddled with

when I was eight.

But don’t worry about that.

Find Victory Drive and turn left,

or turn right if you’re going the other way,

head east toward the ocean.

The Victory was about World War I,

happened over 100 years ago.

We planted magnolias along that drive,

bloom sweet pink, white, and red in February,

gone by March.

But don’t worry about that.

Keep going. Oh, stop for crabs in Thunderbolt.

I mean eat crabs, not crabs foaming over the road

or some weird Biblical shit like that.

Eat crabs if you want but then keep driving

over the stacked stone bridges, five of ‘em,

won’t turn sideways on gears,

five monuments to junked machinery.

Now it’s time to worry a little.

Along that flat part past the ruins of Fort Pulaski,

it’s been merging with the marsh at high tide. Swamped

is what it’s being, reclaimed

up from Florida by the alligators and the pythons,

“for behold, I will send serpents.”

Those slimy bastards never dared that

when I was a kid, but the oceans,

they’re on the rise, oops,

shush that, that’s

blasphemy.

Don’t worry about that.

You’ll get to the beach if you don’t flood out.

Beach’ll still there

like I told you.

Those condos though.

Those condos are toast.

Don’t worry about them.

Drive around south and look west,

hell of a bloody sunset over the sandbar.

That’s where my Aunt Bea

used to hang her bait for crabs.

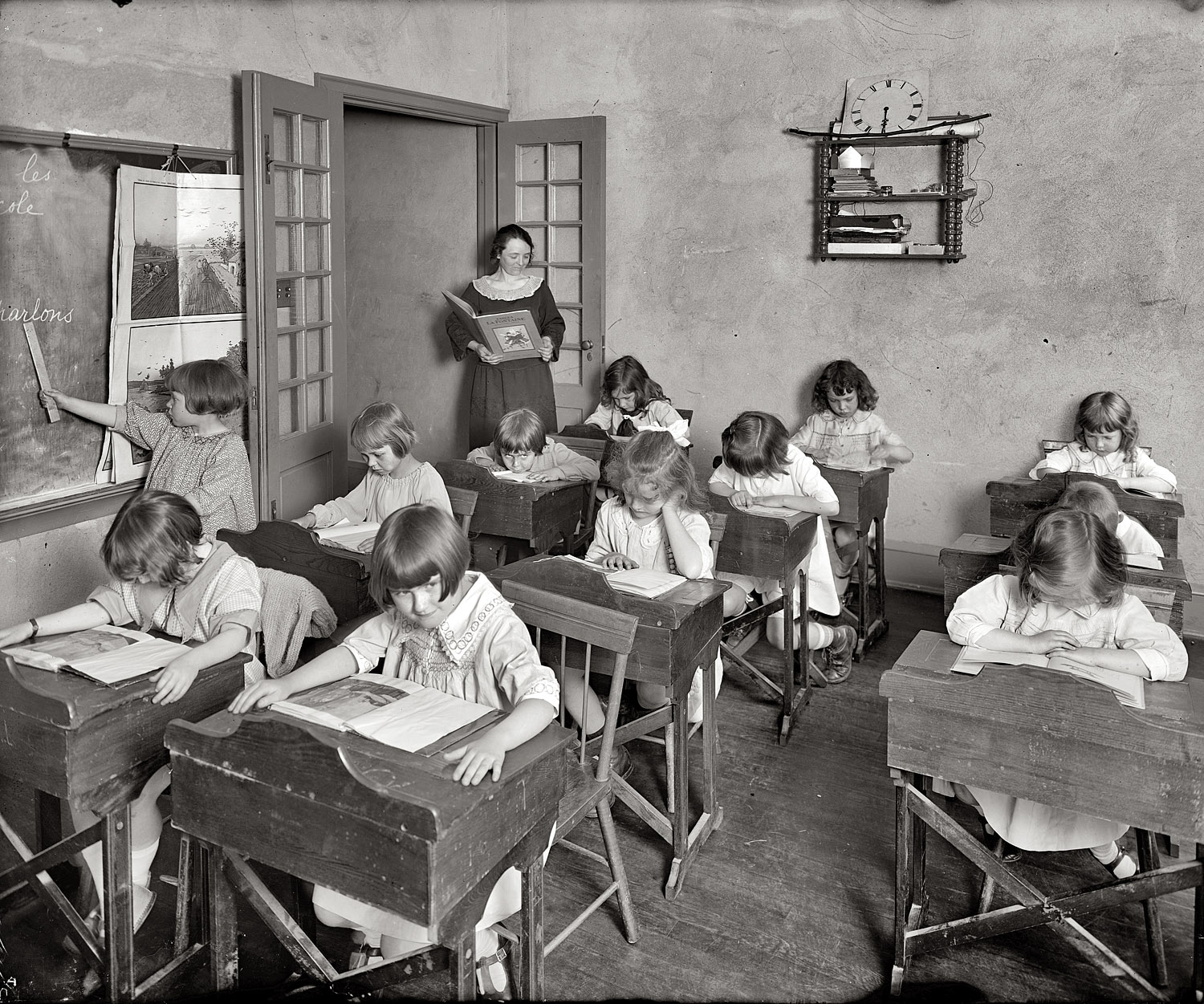

MASSEY SCHOOL BUILT IN 1856 ON THE PATTERN OF AN ANCIENT GREEK TEMPLE

The golden ratio can be used to fashion brick

to classic balance and perfect symmetry.

A temple for learning and reason,

built for the sons of honest sons of Englishmen

by the enslaved. But even the glorious Greeks

had slaves. Even Thomas Jefferson could not give up

the warm comfort of his cradle-to-grave

slaves. Some things are just too compelling to let go,

like cane sugar, like broadleaf tobacco, like

incest, those fathered by their masters

and later used, as the custom used to be.

Aren’t we all servants of some institutions,

masters of others? The bricks of the temple

can align with lunatic lines of logic

as the sun sets and the mortar shimmers

with whatever liquid has been spilt to mix it.

Rain darkens the brick in December, not

just the walls but the sidewalks are brick, even

some Savannah graves are built of bricks,

but who favors graves, save martyred souls, and

everybody’s too polite to bring them up

at civilized congregations.

I had a third-grade girlfriend at Massey School,

Linda Kay. She told the teacher, crying, begging

not to be kept after school, that her mother

whipped her with a garden hose. It took me

fifty years of puzzling to realize she meant

a hose truncheon like those used by interrogators.

The image I had then was of Linda Kay’s mother

wielding a long hose, like a circus act:

Amazing 20-foot garden-hose whipping-

the-Linda-Kay extravaganza.

We’ve all borne our whippings and swallowed the harm.

The brick may sweat children’s blood, but

it washes away in the rain.

You can still enjoy the classic symmetry

Massey School still standing there on Gordon Street.

SORRY, I’VE GOT TO GO

Malo Mori Quam Foedari*

— Payne Family Motto

The sun hits the wall of the little nest

my new wife, Ann, has made of our flat

on Bishop Street, and the light angles

across the old pine floor. March wind

flexes the plastic tacked to the windows,

but Heather, wise in the ways of cats,

has curled up in a plank of sun, and sleeps.

I’m holding the just-arrived with no stamp

single-page onionskin government letter.

Despite jokes and rumors, it doesn’t say “Greetings.”

I’m frozen.

Carol King looks across barefoot from her record cover.

Dylan’s head explodes with psychedelic delirium,

a poster we’ve thumbtacked over our mattress.

Heather yawns and stretches.

We’ve argued all year about Canada

or prison, the hard moral choices,

or that psychiatrist in Boston who’ll write

insane diagnoses, or other even more

convoluted options.

All that hot talk now stilled

by this one thin blade of ice.

Somewhere in me, old blood

pumps with martial obligation.

It’s so stupid—it’s not even the right war—but no

choice, never had one. This translucent typed order

nullifies evasion.

I know I’ll let them take me.

* I choose death over dishonor.

A SANDSPUR

magnified is a rod of spikes.

I know. I rigged the photomicrograph they used

in the Valdosta High School yearbook for years after I fled.

An eccentric icon for a high school,

you might say, but a certain rough humor

was de rigueur in that territory.

Backlighted, it’s strangely translucent. The stem

leads upward on a slant, the barbs appear

too rounded at this magnification to penetrate,

but they’ll stick fine at their own scale,

as you try to clear your socks

or your brain,

whichever the most compelling penetration.

There was Coach K who liked ripe reddened

boy asses. I hated his grin. He got run

out of town sometime around 1961.

And the thirty-year-tenured Bible-quoting

Miss R who gave girls A’s, boys D’s,

finally fired, finally, the year before the year

she would have spiked me on her D.

Sandspur sap flows hard with why complain

when you’ll be the one gets the blame.

But like I say, you had to take hold of the humor

as you ended each day picking out the sharp

spine-covered burrs.