Southern Legitimacy Statement: I was born and raised in Missouri and now live (very, very) close to Atlanta. With the exception of college, I have spent my entire life in the South. I most certainly do not miss the snow, or the cold.

How Many Dead People Does It Take to Drive in the HOV Lane?

Roughly four years ago, I had a state issued permit to transport the John Does of unidentifiable fame from a large hospital in Atlanta, Georgia to a nearby county coroner. In doing so, he would authorize the payment of $75 per. In accepting these assignments, I guaranteed a fresh supply of cadavers for local medical student’s lab work under the coroner’s supervision. It was easy money on my part.

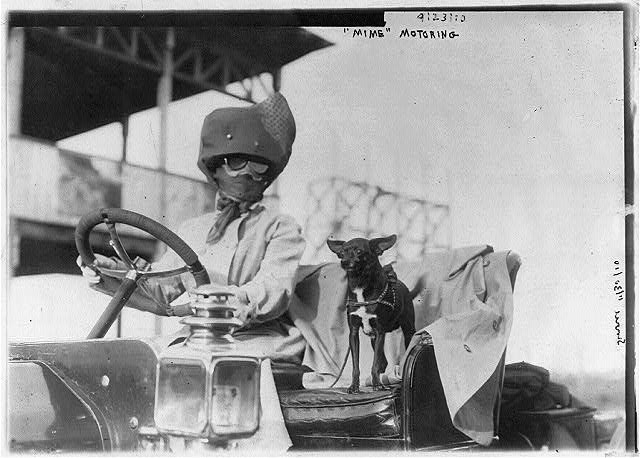

I placed a successful bid for the removal of four cadavers. Upon arrival, the coroner called ahead and asked the hospital staff to prepare six (not four) for removal. Realizing a fiscal opportunity when I saw one, I amended my paperwork and began the process of loading. I carried each cadaver to my truck and secured each in accordance to state laws. However, the sixth passenger did not fit puzzle-piece fashion (this is an occupational term for partially defrosted, malleable, dense-packed cargo space occupants). So in order to expedite my delivery, I relocated the sixth to the front seat of my truck (still in a standard – water tight – hospital body bag) and secured him with the shoulder strap seat belt. Because the day was overcast, “Sixth” wore my goggles and hat to prevent either from breaking or creasing. Since I was now twenty minutes behind schedule, I opted for the non-traditional route of the local interstate highway and its newly refurbished HOV (high occupancy vehicle) lanes on the “Downtown Connector” (the fusion of I-75 and I-85) to shorten the trip and make my delivery on time.

The state police did not subscribe to my POV when they pulled me over for a HOV lane violation. Officer Perkins (the names have been changed to protect the innocent) stated that the spirit of the law required all passengers had to be currently alive to use the HOV lanes. I countered with the letter of the law did not make such a distinction. Apparently, two years in high school debate class does not make one a well-received orator in the eyes of the law.

Arrested, with my truck impounded, I demanded an immediate bench trial (considering the time stamp and the rate of thaw) and was granted my request.

By 1pm, right after lunch, standing in front of the bench of a traffic judge, oblivious to the extent of the pre-trial publicity of today’s docket, and the focused attention of a myriad of courthouse personnel, both Officer Perkins and myself made our cases. I remained dignified to match Officer Perkins amid a growing amount of smirking from the bailiff, the stenographer, and clerks. The judge did not share their esprit de corps for the proceedings. He also looked peeved at being ambushed and certainly wanted an excuse to recuse himself from the case. However, neither Officer Perkins, nor myself could yield our legal high ground. Only a ruling from the bench would settle this impending Constitutional Crisis.

The judge offered a deal to me. My permit would expire soon. He said that if I pleaded nolo-contendere, he would drop all charges and allow me to finish my delivery without any court or impound fees. If I didn’t, he explained the renewal of my permit would exceed my financial capacity to continue in my current occupation. I acquiesced, made the plea, shook hands, and drove to the waiting coroner.

The judge also ordered Officer Perkins to escort me as far as the county line (these six miles in downtown, rush hour – it always is rush hour in Atlanta – shaved another hour from my belated ETA). Needless to say, Officer Perkins followed his orders to the letter.

The final paperwork concerning my plea deal arrived in the mail within a week. Nowhere did the judge list the terms of the deal or the legal precedent to make his final decision. I did not care, for 6 times $75 plus a story made this delivery (and the associated story) worthwhile.