Southern Legitimacy Statement: … born and raised in Austin, Texas. After a few years in Memphis, Tennessee, she now calls Austin home again. Here, she works with Austin Bat Refuge, rehabilitating winged creatures on their way further south for winter and full-time Texas resident bats as well.

My Friend, the Doorstop

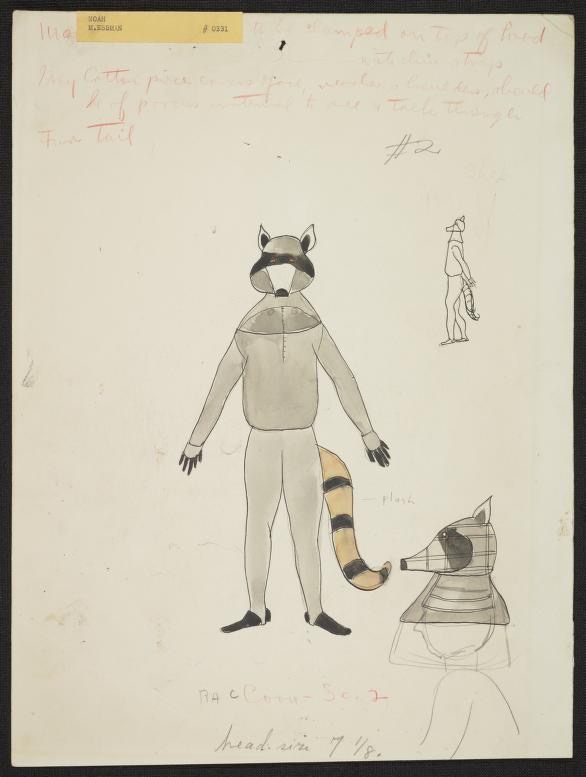

The raccoon is one of a thousand things that has never changed in that house. He lives on the bathroom floor. His limp body on the linoleum, matted fur resting against faux tiles and shineless eyes staring along lines of vinyl grout.

In the dining room, the Virgin Mary watches over the meatloaf and potatoes from her perch on the wall where she’s always been. I remember my Mom once saying, “Catholicism does emphasize Mary’s importance more than other sects of Christianity. That’s at least something.” And then I think of her saying, “You can’t tell him we’re not Catholic anymore or else he might have a heart attack and die.” But that might’ve been something she said with her eyes and not her mouth.

Either way, I got the message. I say Grace. My grandpa doesn’t have a heart attack. He’s creeping up on ninety-three and I’m staring down twenty-two and six months and I’m gay and he doesn’t know that and I don’t go to church and he doesn’t know that because one thing about pretending to be Catholic for a few hours on a Tuesday night is that it’s really not that hard. It requires a bless us oh lord and a these thy gifts which we are about to receive, but sooner than you know it you’ve made it to amen.

Then we’re all working our way through our pools of ketchup and corn-water under the watchful eye of the Mother of God, and Grandpa’s reminiscing. He doesn’t remember how to play that one card game; that bothers him, he admits. Everyone he ever played the game with is dead now. That bothers him as well. That’s the thing about change out here: it’s usually synonymous with death.

We move on quickly. “Blair, when are you getting married?” He’s being facetious. Everyone laughs, especially my brother.

In the car on the way here, we speculated on how long it would take him to ask this new favorite question. “He doesn’t mean anything by it,” assures my brother. “He’s just gotten old and started saying whatever he wants.” Right. But at the same time, his jokes are laced with an earnest belief that all women should be some version of a house-wife. That notion makes my skin crawl.

“Your guess is as good as mine,” I tell my grandpa, even though what I want to say is I’m sure you’ll be dead by then. The raccoon listens through old polyester ears from a room away. I decide now’s as good a time as any to pay him a visit.

I round the corner and there he is, holding the door open like the gentleman he is. I kick him out of the way and let the door swing closed. Now it’s just me and the racoon framed by a sunflower shower curtain and the smell of baby powder. He’s good company, limp and lifeless on the floor next to the space heater’s open flame.

Across from my raccoon lives the sink. And in the sink lives the ghost of a scorpion. I was three or five or eight, freshly out of the shower, grandma coaxing my fine hair through the circular brush that was a staple of sleepovers on the farm. Before she’s done with my hair, the scorpion in the sink begs to be addressed. Or at least, I beg for it to. Grandma obliges. She proves once again that her hands are invincible – unscathed by hot pans and years of kneading dough and wringing necks of chickens.

I was raised on grandma’s cookies and kolaches and rolls and love. I was raised on watered down iced tea in her kitchen and kneeling to pray over the lumpy futon in the back room before bed. I was raised on the same story read from the same bible every Christmas and the echoes of my three dead uncles in photos and names and soft smiles. But all the while, there were conversations happening in the background that I was none the wiser to. If you ever say bigoted things about Muslims around my children again, that’ll be the last time you see them, my mom said.

When dinner’s over grandma says, “Thank you for coming. Come by whenever. We’re here all the time.” And something about the way she says it makes the air feel different on my cheeks and it makes me feel bad for years of judgement and it makes my brother saying, “We’ll come back soon,” sound less like a white lie than I’d expected it to. I wave goodbye and say I love you and mean it.

Next time we’re back, I’ll visit my friend the raccoon, who never says anything I disagree with. I’ll smile down at him. You look terrible, my friend. It’s said that all the grandchildren will get some land when grandma and grandpa die. I’ll probably give mine to my brother. I’m much more concerned about who’s going to get the raccoon.