Southern Legitimacy Statement: I was born in Jacksonville, Florida, have lived in Asheville, North Carolina, for over thirty years, and feel most at home on the Tybee Island beach.

Hometown Lies

“No soy de Miami, pero mi abuela es de Cuba,” I write in the chat at the Zoom board meeting, responding to my Cuban colleague’s lament over her friend’s return to Miami.

“Oh! You’re Cuban!!” she writes back. I respond with a heart emoji and vow to pay more attention to the meeting. Backchanneling was made for people like me and perhaps my Cuban colleague. People who always have something to say. People who have learned to keep quiet, to not interrupt, but desperately want some way to hurl a barrage of Yeses, Amens, applause, hearts, and party blowers into every conversation. And I’m actually good at typing in the chat and still paying attention. My husband, a mathematician, reminds me that multitasking is scientifically impossible. Maybe for him.

But I quiet down, restrain my itchy fingers, and content myself with being mistaken for a Latina. The truth, I tell myself, is that I’m not. I’m white. Unquestionably white. I have blue eyes and blonde hair and am accustomed to the privilege that accompanies my visible identity. My olive skin is the only hint that my family didn’t originate in Northern Europe.

I remember the first time I felt confused about my identity. I was seventeen and filling out the FAFSA for college. There were only two options: Hispanic or Non-Hispanic. I’d never considered myself Hispanic, but I had grown up listening to my mom and nana argue incessantly in Spanish. I spoke Spanglish at best, Spanish words and phrases peppering my thoughts and speech. Checking the Hispanic box would have been a lie, I knew. Where was the box for Italian-Cuban-Russian? Where was the box for “I’ve met the people in my family who came to this country? Beautiful people with beautiful, terrible stories?” Not on the FAFSA form in 1994. I looked to my mom for guidance, but she shrugged her shoulders. In what felt like a life-defining moment, I checked the Non-Hispanic box and moved on. I had never been oppressed because of where my grandmother was born, and it felt unfair to put myself in the running for funding based on invisible cultural heritage.

Landing in Asheville, North Carolina, as a teenager didn’t help my confusion. I know. Poor me. My family moved to one of the most desirable spots on the East Coast back when housing was still affordable. Now, people flock in droves to this city I hesitate to call home. And I get it. The mountains are gorgeous. The waterfalls are breathtaking. The streets are fringed with art and food and a vibrancy not found in most cities Asheville’s size. I landed in an ideal spot, and I’ve lived here for over thirty years. But as a kid, when people asked where I was from, I’d shrug and say, “My family’s from New Jersey.”

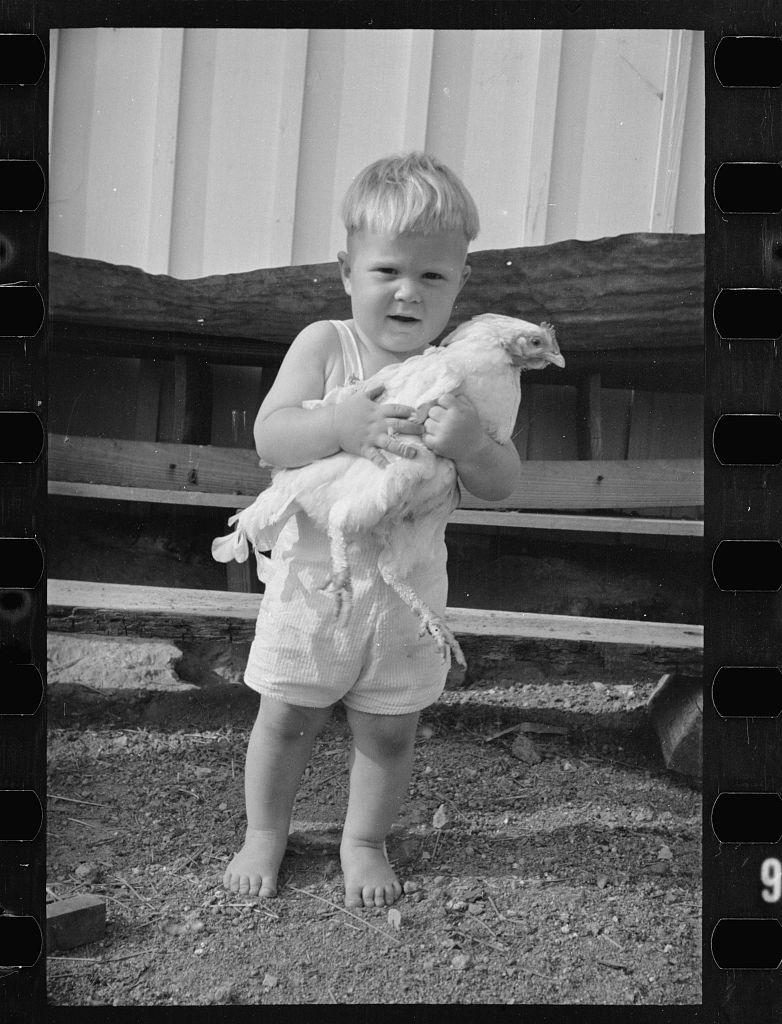

There’s nothing wrong with Asheville. In many ways, I’m what people expect when they think about this place: artsy, white, liberal. I’ve brewed my own beer and kombucha. I hike, paddle, run, practice yoga. I have two dogs, three cats, backyard chickens, and a neighborhood bear I call Peter. I love good food and grow what I can in a side-yard container garden. I teach at a Liberal Arts university, and I focus my courses around social issues and community engagement.

But of course, we all came from somewhere else. I didn’t spring from this land any more than all the other faux-Ashevillians. “My family’s from New Jersey” wasn’t a lie, but it was far from the whole truth. It was a non-answer. A refusal to respond to a question that confused me and an attempt to explain the complexity. What I wouldn’t say unless pressed is that I’ve never lived in New Jersey. I’ve lived in Arizona, Washington State, Florida and Georgia twice, multiple cities in North Carolina, but I’ve never lived in New Jersey. I love New York City, but don’t feel particularly comfortable in the Northeast in general. I love snow, but I hate the cold and feel much more at home under the sweltering Savannah sun. But I’ve found that something about New Jersey helps to explain my existence, especially for Southerners.

While we were moving around from state to state every couple of years during my childhood–I had twelve addresses before I was ten years old–returning to Hackensack, New Jersey, for Christmas, sometimes Easter, was the only constant. When we moved to the funky little mountain town that Asheville was back in the mid-eighties and I started middle school out in one of the county school districts, explaining that my family was from New Jersey was the only way the other kids could make sense of me. “Oh,” they would nod, “you’re a Yankee.” Well, not really, but it worked. It explained why my dad got upset when we went to the bakery at the local Ingles, asked for hard rolls, and the woman behind the counter, after looking at him funny for a few minutes, gave him a bag of day-old bread. It explained why nobody at the pizza place on Smokey Park Mountain Highway knew what my mom wanted when she ordered two pies with pepperoni and black olives. It also explained why we didn’t go to one of the many Baptist or Methodist churches out in Candler where we lived, but drove half an hour south to one of the few Catholic churches in town.

When I started dating, a boyfriend invited me to his Memaw’s house in Old Fort, North Carolina, for Thanksgiving. I had never met a memaw before, but I loved this tiny woman from the moment she took my hand and proudly led me to the bathroom her grandsons had just built out on her back porch so she didn’t have to walk to the outhouse on cold nights. Memaw seemed to like me, but everyone else just stared. I tried to settle on the couch to mutterings too loud to ignore: “She looks kinda exotic,” “What is she, some movie star?” “I’m from New Jersey, just outside of New York City,” I finally announced and everyone relaxed, nodding, “Ahhhh….” Now I made sense.

If you know anything about the part of New Jersey “just outside of New York City,” you know this is not a cosmopolitan brag. My people didn’t summer on the shore, they didn’t even vacation at the beach. We’re not from Connecticut or Vermont. We’re from the part of Northern New Jersey where cops patrol small towns packed one against another, each with its own ethnic flavor. My dad barely made it through high school, working nights at a liquor store to support his mom and sister after his dad died when he was fourteen. My mother’s father, Papa, was a draftsman, but before him, the men in his family were immigrants working in dress shops, cutting hair, fixing cars.

My mother and Cuban grandmother, of course, spoke Spanish to my great-grandmother, Abuela, and whenever they didn’t want my brother and sisters and I to know what they were saying. My father’s family celebrated Russian Christmas at the orthodox church down the street from my Aunt Jules and Uncle Joe’s house and caroled around what my mom still calls “the Russian ghetto” with songs from the old country in a language I don’t understand. My Little Grandma, my Papa’s mother, made such beautiful Italian food that I still have a hard time going out for Italian. I’ve been told to “Mangia! Mangia!” since I was old enough to sit in a highchair pulled up to her plastic-covered dinner table.

Back in the board meeting, I apologize–as I always do–for talking too much. My colleague jumps in, “That’s what we Cubans do–we interrupt!” She exonerates me, and in that moment, I feel seen, recognized. Coming of age in Asheville, a predominately white city, attending predominantly white churches and schools, I’d never known why I felt so different when I looked pretty much like everyone else. I started understanding the culture clash around the time my first marriage fell apart. “Didn’t anyone ever tell you it’s rude to interrupt?” my ex-husband would demand, never mind he’d monopolized the conversation for the past ten minutes. “Doesn’t anyone in your family ever feel so passionate about something they have to cut in?” I hurled back. “It’s like a compliment,” I would try to explain, “like you’re so invested in the conversation, you can’t contain yourself.” But in our relationship, my passion was never an asset, just a liability, a challenge to what he’d always held as true. Too late to save my marriage, my Cuban colleague confirms what I suspected–this is my truth, my identity. I may not be Cuban, but all these bits and pieces make me who I am.

I’ve stopped saying, “My family is from New Jersey.” Now I just wonder how many of us walk around Asheville like I do, our invisible selves suffocating from lack of air, lack of recognition. As we craft these places of perfection, design schools and communities that reflect our evolving, sanitized sensibilities, how do we retain the complexity of ourselves? How do we share the vibrancy of our stories in these cultivated, white-washed spaces? How many of us are waiting, perhaps unknowingly, for a colleague on Zoom to help us know ourselves?