SLS I was born, like everyone else, in a particular place. Alabama: not just a Southern state, but The Heart of Dixie, where vowels are long and round. I spent my early years in the woods (without a gun) searching for answers to how the universe works to explain to myself how I could survive it. People around me told stories to each other to get close to each other, to make religion stick to our bones like mashed potatoes, and to pass the time. Now I live in Atlanta where we all pretend to be more sophisticated, but we understand that the universe is not really any different here. The particulars are always different, but from far enough away, we all look the same.

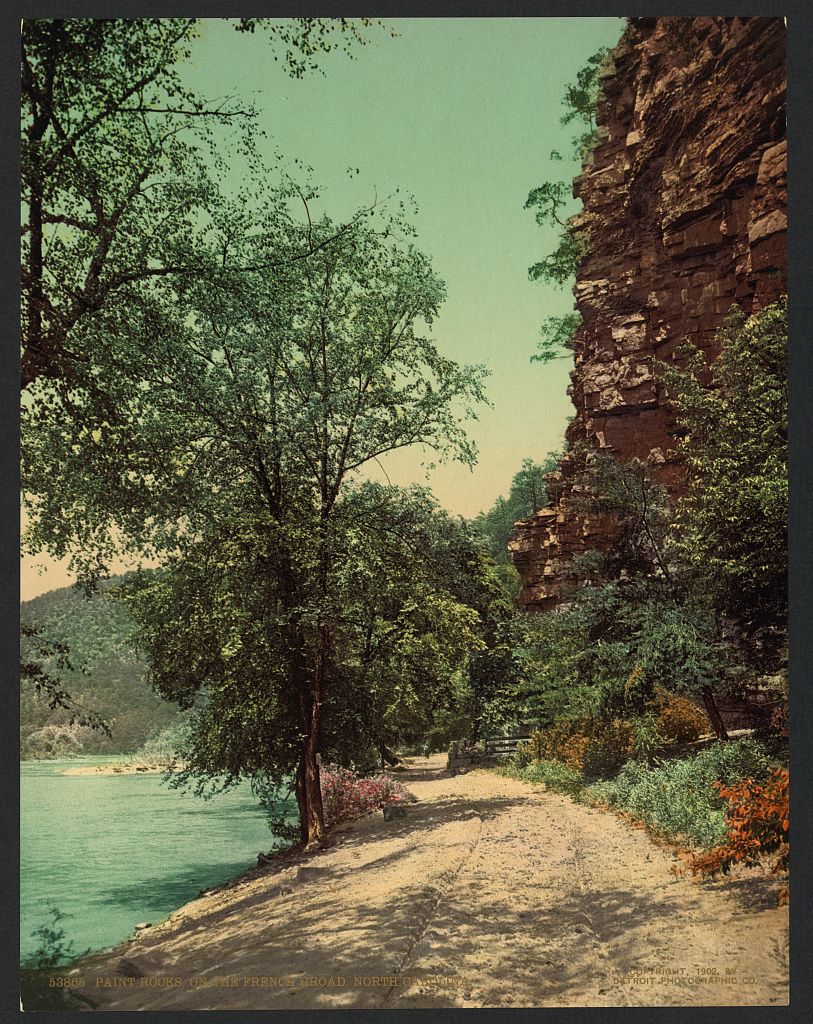

Rowan Oak

Large, airy rooms gather sunlight between cypress limbs,

sprinkle it across the thick wooden floors and wool carpets,

and I stand behind the curved Plexiglas to look at your bedroom,

no longer private: riding boots, hunting guns, a manual typewriter

gracing a small wooden desk like a cross on an altar for all to see.

I curse the barrier, yearn to laze across the blue bedspread

and study those red-grease-pencil days of the week

from underneath. Better yet, to stand in my socked feet

on that same quilt, and rub my fingerprint

over the letters, smudging a mixture of your work

and my life: a collaboration across the years.

I find my father’s picture, show it to a travel companion,

remark on the likeness between him and you,

claim some cause for the strange power of connection

I have to long, winding sentences and the agony of loving

magnolia trees. I own those dirty underpants;

I have never been able to see an ear of corn innocently.

When I was pregnant, I thought of Addie’s twoness

and marveled that a man could have understood.

I covet the lives of those friends who have given up

their day jobs to live with words, as you did,

sleeping under the guidance and haunting of their scribbles.

I see that there were servants in this house,

that writing and art too often comes from those

who starve or have other means not to starve.

I curse the paycheck that paid for my trip to visit this.

Madness dances with me across the threshold

and back down the unpaved driveway.

I look back over my shoulder

for one more camera-phone shot of the imposing porch.

The structure, such a Faulknerian sentence,

lures me to come inside without letting me touch.

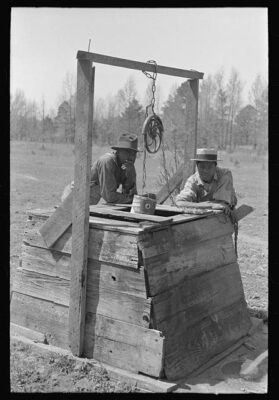

Early Summer Babysitter

I swing my feet over my parent’s garden;

he pushes me from behind, his long

hands on my favorite superman t-shirt.

Under my toes rows of corn, strawberries, squash;

my nail-bitten hands grip the black nylon rope

that holds a round wooden seat to the live oak tree.

He’s sixteen, so he talks about television shows,

and I’m six, so I pretend to know them all.

Between our chatter, the world flies past

in blurs of bark, falling green leaves, and a white sky.

I want to stop, put my feet onto the brown soil,

to make sure that the summer air bakes

this memory into ashes.

Mom told him that I like to swing,

so he stands in the tall summer grass and pushes me

over the garden—over okra and snap beans

and I lie to him about what I know, what I like,

and he smiles when he pretends to enjoy pushing me.

We have all day to kill, and we don’t know

each other well enough to know the difference;

I smile and giggle like I’ve been taught to do

when the swing makes me fly into the sky.

He asks if I want to go higher; I say yes

meaning no, meaning I’ve had enough,

but I know that nothing edible grows in air.

He mentions One Day at a Time and a girl named Valerie,

and I look over to the neighbor’s barn to the hay bales

stacked neatly inside; their softness spoiled

by fingers prodding. I wish I could make

a single leap from swing to loft or air

or could speed past him and into the garden.

I want to run down the rows of corn, the leaves

of the towering stalks slapping my face;

I want to hide myself in the camouflage

of silk tassels and the ears that forgive my forming screams.

Storm Wake

Resting in the eye of Fredric, 1979,

I listened to the stillness, the silent groans

of oak trees hammered by insane air and water.

I soaked up the calm of a once dangerous house,

now quiet and sleeping.

Sky reappeared; the stars remained unaffected.

But as I looked up, I knew all would be changed

when sunlight showed me the source of the pelting

pine-sap smell, the fresh scent of twisted trunks

and unearthed roots.

The eye passed.

Wind ripped shingles like hair from a scalp;

rain seeped under every door

and overtook towels stuffed to keep it out.

I lost the sky, my bearings, all sense of a safe world.

Windows cracked like jawbones;

fences crumbled into heaps of mangled flesh

in another woman’s garden.

He howled like a madman;

his fingers pushed over fort, sandbox, and oak tree swing.

He battered cars, mailboxes, and satellite dishes.

When his anger finally passed over,

the sun crept out again, somewhat timid.

In the morning, she showed me my coastal town,

and I, unwilling to acknowledge his terror,

grabbed up the chainsaw and cleared away the evidence.

It was like pouring make up on a bruise.

I thought I could make it okay.

I thought no one would notice.