Southern Legitimacy Statement: I was born north of the Mason-Dixon line, but with a Southern spirit. Now I’m happily settled where Southern red cedar bedecked in Spanish moss shares the landscape with live oaks and cabbage palms—Florida,the land of flowers, where it’s harder to stop something from growing than to start it.

Luck of the Irish

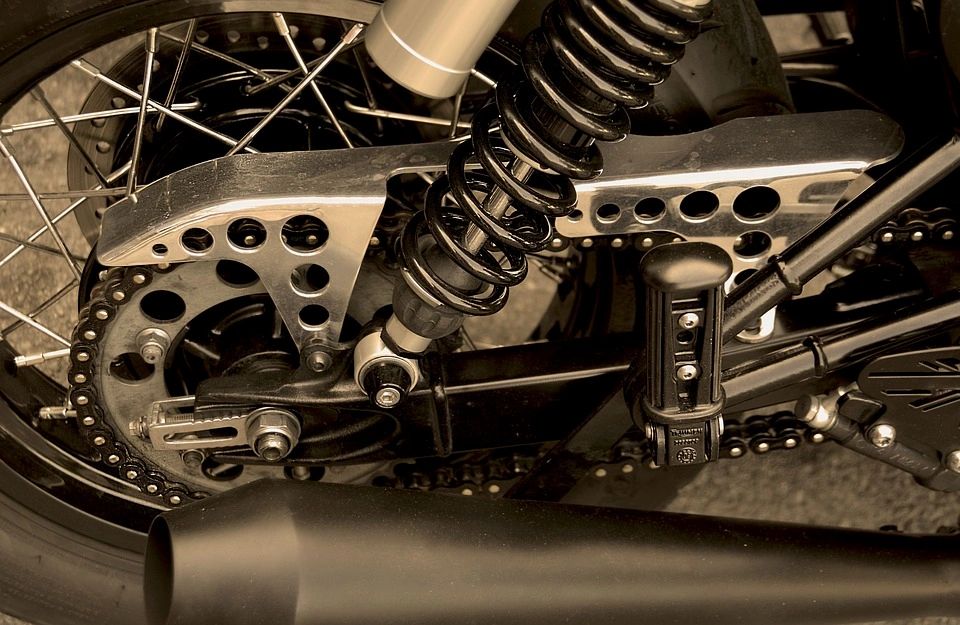

A song walked past my house today—struggled, staggered, actually—in the form of a young woman. She passed me while I was pulling weeds near the street. She was straining, leaning nearly sideways—a fulcrum against the weight of the old motorcycle she was struggling to keep upright as she pushed it down the road. The oppressive Florida heat was adding to her burden.

“Oh, my goodness!” I called out. “Stop and rest. What happened?” The words tumbled out of my mouth as she was nearing the imaginary line that would take her past my property, my invisible sphere of influence.

“Luck of the Irish,” she answered simply. She paused, considering, and then laid the bike down and looked over at me. She didn’t have an Irish accent, but she could have stepped straight from an ad for Aer Lingus. She was dressed in blue jeans and a rust-colored shirt that didn’t suit the temperature, due to hit triple digits by noon. She was striking.

“Can I get you some water?” I offered awkwardly. I wasn’t sure she’d accept—the pandemic and all.

“I was just thinking of how wonderful some water would be. If you have it in a bottle, I’ll take it,” she replied, practically. I rushed back in the house to grab a cold bottle of water. I called to my husband—maybe he could help with the motorcycle? I didn’t wait to see if he heard me. I was afraid she might disappear if I weren’t fast enough.

She downed the water. “Are you from Florida?” she asked me. I shook my head. “I am,” she offered. “Born and raised. Florida has a way of making you feel comfortable. It bonds you to it. It’s hard to leave.” Off-handedly she added, “I told myself there might be a problem with my fuel line, but I think my ex drained the gas. I just broke my last bond; it was the hardest one.”

I murmured sympathetically, unable or unwilling to break the closeness that was in the mood and the air. She continued,

“I was a bartender, but they’re not going to hire me back. With this virus, no one’s going out anymore; but I know enough people in Maui. I’m going to take the leap. I’m headed back to my hometown today…a last hurrah, and then I’m going to take the leap, Maui.”

My husband came out with a gas can and funnel. He filled up the tank, and they talked motorcycles for a minute or two. She tossed the empty water bottle into the neighbor’s garbage can, glancing first to see if it were the proper can. It wasn’t, so she tossed it in with yard waste and I resisted the urge to retrieve it. She straddled the big bike and turned the throttle. It sputtered a few times and then rumbled to life. She started down the street.

“Good luck!” I yelled after her. Then added, “Don’t look back!” She didn’t. We watched her go, then both lamented the fact that we hadn’t given her any money.

“A person could write a song about her,” my husband said. I nodded, musing.

He went inside, and soon I heard him trying out some riffs, a few power chords—the seeds of a new song. The music proffered its theme–liberation, the open road—pure rock and roll.

A song walked past my house today. I think it was the blues.