The City Jail

The City Jail spiked out of Fifth Avenue

in the heart of downtown Pittsburgh.

When we drove by it, my father would pause

and signify in its direction,

never uttering a word. Riding shotgun,

my mother on cue blurted she’d glimpsed

our imaginary condemned prisoner

in the jail’s uppermost barred window.

From his cell, four stories high, he looked down

and spied me. Dressed in drab fatigue—

like Duquesne Light’s meter reader

who snuck through the alley with his tablet,

tallying each spark of power we consumed—

he waited to be strapped in the electric chair.

In the back seat with my sister—mesmerized

by Dickens, so good she had no worries

about retribution – I craned up to see him

and exclaimed, though I can’t fathom why,

There he is.

My mother, unblinking, pursed mouth,

eyebrows fixed like an empress’s,

looked at me as if to say:

Yes, of course, he’s there

and now you’ve seen him.

For a boy like me –

straight F’s in Christian Doctrine,

scarlet U’s in conduct,

a boy who faced at best hard time

in Purgatory – the meaning jails held

was abundantly clear.

There were places if you faltered: Juvie,

Thorn Hill, Morganza, St. Joseph’s

Military Academy. Bread and water,

rubber hoses. Guards and guns,

ropes and chains – crueler than nuns,

darker than confessionals.

They’d come and take you away,

give you the electric chair, the gas chamber.

They’d chop your head off.

I was certain I’d never escape the City Jail,

my next detention after maxing out

of the 19th century brick schoolhouse

in which, day after day, I built time,

parsing venial from mortal before bearing

false witness about my sins to the Jesuit

in his long black cassock and purple stole.

I made the Sign of the Cross when passing

the jail, like passing a cathedral—

some small indulgence in it, I prayed, perhaps

a notch or two, off my sentence—

bowing my head, hammering my heart.

Mea maxima culpa.

It truly was my most grievous fault—

whatever I had done.

It was just a game—about the man

in the jail window—a terrifying game,

like catechism, the adults admired—

to turn you good – their wizened parable.

My parents thought me merely playing along,

like claiming to have witnessed my guardian

angel, or Santa beating it up the flue,

simply trying to please them—

not that the true reckoning of that man

on Fifth Avenue enveloped me

in black, like the last smoky flicker

swinging on its drowning taper-wick.

They’d break into smiles,

Marie’s head dipped back to Bleak House.

There was nothing to be afraid of.

Years later, I would leave my parents and sister,

slip silently out of my father’s Chrysler

into my own car and steer it out of Pittsburgh,

South, to work in a prison, past the City Jail

where that man still draped his window,

longing for the executioner’s hood

to drop over his head. Occasionally,

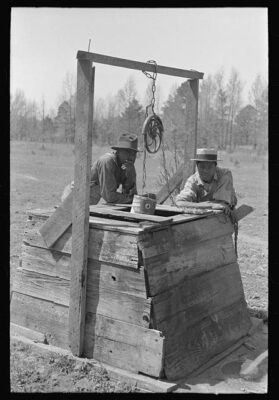

I’d see him, bone-shackled, straddling

a ditch along a Carolina county roadbed, swinging

a bushaxe, pounding bedrock to ash.

He had the addled ice eyes of the lightening-

struck, crosshairs stitched on his forehead.

He never failed to recognize me.

**

Lost Dog Fox Litany

—for Jim Harrison

I’ve been over this ground.

The Bible says nothing of foxes

though the Psalms urge sustained inquiry

into the nature of mercy.

At a predestined moment

winter weds autumn

with its dowry of chaff.

Each season the earth

rearranges itself. The lost dog

follows a path that leads

no longer home.

The ridge barbed wire once hyphenated

has slipped into the nameless

creek. Silence trickles in its bed.

Twisted into a rusted epigraph,

the ruined fence insists,

“This is not about you.”

The dog, a salacious blonde

with a purple tongue, is a widow.

I dug her husband’s grave with an axe.

He died in the odor of sanctity,

defending his wife’s virtue.

High in a red oak, the kestrel,

bloody beak tucked in sable ruff,

devours a baby squirrel. Hiddenite

veins a creek larch. Viridescent.

This is where I found

an arrowhead from the now extinct

Yadkin tribe. It is older than Jesus

by 1200 years.

The rain will never stop.

The firmament, like dishwater,

casts a pearly light.

Slashes of deer prints

and the rain-glazed selaginella

are like the divigations of Chinese painting.

Trees open their legs at the root saddles.

I no longer mind the sky’s incessant weeping.

I crawl into the cleft

left in the creek wall where a Maple

walked off the earth, leaving

behind a root Medusa

studded with tiny eggs of mica and feldspar.

There I say my daily rosary

as commanded in a vision by God.

Held in the severed roots

of a dead tree like Yeshua

in the arms of his astounded virgin

mother, I wonder

whatever happened to Saint Joseph.

Oh, Greta, Greta,

where is my lost girl dog?

If Clara Bow had been a canine…

Foxy.

On hands and knees I sidle to a vein

of sylvanite, a mineral which when it occurs

crystalizes into penmanship.

Odd to see God’s name

misspelled in rock on a creek floor.

In the woods you know when

a creature is on the move.

The snap and sibilance,

the deliberate fourness

of its perfectly iambic gait.

Yes.

There’s my sweet girl.

The water glowing amber with her furry reflection.

I’ll name this creek later.

Looking up, the most instinctive gesture

a crawling man can perform,

I see not my dog, but a red fox so perfect

it must not be a red fox, but a drawing

of a red fox in a child’s picture book.

Instantly I become a drawing

of a man in a child’s picture book,

trying to think of a moral, a witty rhyme,

but frankly I’m afraid.

Foxes do bad things to men in books.

Its fox beauty is disorienting,

shrewd brown eyes

too much like my mother’s.

On my internal tape deck, Sylvia Plath,

in her necromancing brogue, drones:

“This is the kingdom of the fading apparition.”

I run, run as fast as I can,

up a bank of juniper root rungs into a burr brake,

the fox doing the same

in the opposite direction after her

decidedly filmic doubletake.

The Freudian implications of this

reoccurring dream – if dream it be –

have me spooked.

I’ve been threatening for years

to enter into therapy

or join the Y,

but cannot justify the expense.

The Yadkin would not worry about this.

They had no word for neurotic.

When finally I stop running,

I stand on a hillock,

make myself cruciate in the dark light

and laughing mizzle, close my eyes

and pray for my dog’s return.

John’s Gospel makes plain

this approach is foolproof.