My Southern Statement I was born in South Carolina where I loved to snack on barbecue sandwiches with cold slaw on top and fried green tomatoes. My great grandfather fought in the War Between the States (if I said Civil War my father corrected me). He had a mule. That mule is now dead.

A Memoir

( a different approach to the form)

My Southern Childhood: a sequence of one sentence prose poems

ONE

The annual tent revivals were avoided by the town churchgoers, but my friend Rennie Clare and I, curious, crawled under the shrubs between her house and the tent, watched as the preacher screamed about hell while his salvation seekers shouted ‘amen’ and ‘praise the lord’ but, soon bored, we filled his car seat with a stack of dead weeds thinking he might speak in tongues or produce a snake, only to have him take his lord’s name in vain and stomp through the shrubs , flashlight in hand, in search of us, the devil’s cohorts, bellies to ground, shaking.

TWO

Mother was appointed by the other mothers as reluctant chaperone to Ella Ruth, Kay and me for our first group rock and roll show at the Charlotte Coliseum where Chuck Berry did his famous strut, where Jerry Lee screamed out Great Balls of Fire, feet pounding the piano keys, bleached hair waving, followed by Clyde McPhatter’s smooth croon, the mostly 16 or under audience screaming, yet mother sat with her hands folded, calm expression on her face, never once complaining about this teens-gone-crazy world she’d been thrown into.

THREE

During prayer meeting mid-week we sang the gospel hymns deemed too undignified for Sunday service, bookended by a start and end preacher prayer and punctuated by the swish of paper fans with Jesus on them so when I saw Places In The Heart years later, beginning with the hymns of a distant congregation backdropped by a camera scan of wheat-filled plains, I wept, wanting to return to my gospel singing days of innocence.

FOUR

On the Sundays preacher and his wife came to dinner mother asked Alma to wring a chicken’s neck, its headless body running across the yard and driving my big town cousin DeeDee to swear off chicken forever, before being plucked and fried in those days when one chicken, plus home-made biscuits, gravy and garden fresh string beans, was enough to feed a multitude with no expectations for more.

FIVE

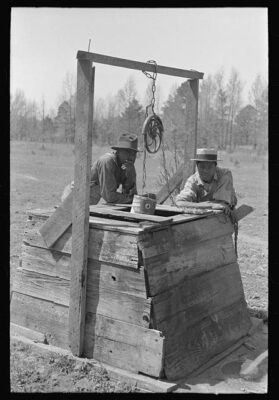

The most cowardly boys and men in town, lions who never bothered to search for their lost courage, would ride through Petersburg, the section where the ‘colored folk’ lived, using the ‘N’ word, throwing bottles, driving everyone like frightened deer deep into the woods of their stores or houses since everybody knew you didn’t fight white folk with the Klan just itching to pull out those hoods for a late night cross burning visit even in those separate but equal days we thought was enlightenment.

SIX

The only big hill in my southern hometown was called ‘Mill Hill’ because that’s where the mill workers lived in their narrow railroad style houses, trudging to work at dawn every morning, returning exhausted by the tedium of their assembly line lives, where two good friends never invited me into their homes there because to them I belonged to that group of people who had everything I could want and might not want them as friends if I saw how different our lives were.

SEVEN

When sleet filled the night, writing cobwebbed patterns onto the windows, my superintendent father rose at four, bundled into his heavy coat and drove the roads checking for school bus safety then called his principals, bus drivers, and a core group of teachers who were assigned to call group of people who had lists , too, in those pre-internet, no tv days, so, soon phones were ringing all over town, waking slumbering dogs and cats, including our own phone, nonstop, with eager voices asking ‘will there be school today?’, me taking the important role of saying ‘no, stay home’ while my father warmed his hands before going back out to waylay any stragglers.

EIGHT

One of five, I took art lessons one summer in Mrs Beason’s art studio beside her house where her monkey screamed through the house windows while we painted identically bad vases of flowers and where, it was said, when she died, monkey poop was piled in burial mounds alongside what was described as a fortune in cash in those days hidden in her mattress, in art books, Southern Living magazines and who knew where else it was, forever gone.

NINE

At our periodic church Fellowship dinners the serving tables groaned beneath fried chicken, peach cobbler, cream pies, string beans, fresh cornbread, jello with grapes and cherries in it, casseroles of every description until we unloaded it into our bellies, then sat, half dosing, while the preacher gave his god bless everybody and everything last forever prayer at the end.

TEN

Like dry cardboard, the cornbread made in the school cafeterias by southern women who should know better, so in that era when we were forced to clean our plates one day I pretended to eat part of mine then sent it flying like a rocket missile down under the long table to its accidental landing at a little boy’s feet who had really eaten his but who was scolded thoroughly for such a disobedient act and my deeply bred Calvinistic guilt for not confessing lingers to this day.