Southern Literature: For five years I taught American literature and creative writing at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, the favorite school of the antebellum aristocracy in the South; I am the author of an award-winning novel about the civil rights movement in Mississippi, The Children Bob Moses Led (Milkweed Editions, twentieth anniversary edition from NewSouth Press), which involved extensive visits to Mississippi, as well as the Martin Luther King Center in Atlanta and other resource sites in the South. Finally, I have been a frequent visitor to various favorite places in the South, including Savannah, Charleston, St. Augustine, Key West, and New Orleans. I have lived in Maryland since 1981.

Preacher Knox

1

There is something compelling

about a man named Moses

walking into a town named Liberty

in Mississippi’s Amite county

(friendship, in French) where

no Black person was free.

That’s what Bob Moses does in 1961,

working to register Black voters.

In late August he lead local farmers,

Curtis Dawson and Alfred Knox,

down to the courthouse to fill out

a daunting registration form.

Suddenly two white men attack,

one hits Moses repeatedly in the temple

with the blunt end of a switch-blade,

knocking him to the sidewalk where

he curls up to protect his head.

Knox, a part-time preacher, tries

to pull Bob’s assailant away while

Dawson pleads with the man to stop.

Moses has a out-of-body experience,

as if he were floating off the ground

and looking down at himself before

coming to, T-shirt drenched in blood.

Knox urges him to leave the scene,

but Moses insists on pressing charges,

entering the courthouse only to learn

that Billy Jack Caston, his attacker,

is the sheriff’s cousin. Against

the odds, Moses files charges.

Back in McComb, Dr. James Anderson

needs nine stiches to sew up Bob’s scalp,

wraps bandages around the wound.

Moses returns to Liberty the next day

for a hearing, the courtroom filled

with white men brandishing shotguns.

Caston claims Moses, crouching

like a kung fu master, attacked him.

The sheriff says it’s too dangerous for Bob

to tell his side of the story. He, Knox,

and Dawson are hurried out a back door,

the judge finds Billy Jack innocent.

2

Thirty years later I drive into Liberty

to research what happened there

during the civil rights movement.

Herbert Lee had been killed at a local

cotton gin, Louis Allen, a witness,

was gunned down in his driveway.

Moses and his fellow SNCC workers

leave the area in 1961; Preacher Knox,

a local farmer, stands his ground,

still lives outside Liberty.

I give him a call, ask if I can come

to his home to tape an interview.

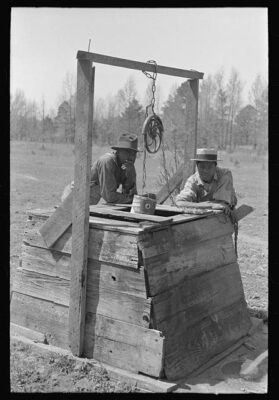

I follow his directions through

a maze of backcountry dirt roads,

no street signs, no names on mailboxes,

eventually I pull up at his house,

a weatherboard cabin with a tin roof,

a stone chimney, a small front porch.

Knox is one of a few Blacks in Liberty

who, thanks to a New Deal program,

buys forty acres of land in 1939,

thus fulfilling a Reconstruction promise

some seventy years too late. We sit on

a bench supported by two large trees.

I remember how the hens cluck

and peck at the front yard dirt.

I place a recorder between us

and as we talk chickens stroll

beneath the bench, still clucking.

A rooster voices his opinion.

A large-framed man wearing blue

denim overalls, a chambray shirt,

Knox explains how hard it is

to be a small farmer: “Ain’t nothin’

folks can do ‘cept scratch it out in

the summer, strap it in the winter.”

When I ask about Moses and Liberty,

Knox calls to his grandson, elbow deep

in a tractor engine: “Come here, Henry,

I don’t think you’ve heard this story.”

A sullen well-built teenager walks

over to us, reluctantly.

As Knox relates in detail

what happened the day he goes

to the Liberty courthouse to “redish,”

the boy’s face changes to respect.

He didn’t know his grandfather

is a hero, stood up to the man.

As we are talking I notice

pickup trucks cruising by more

frequently than you’d expect on

a back country road. Are they

other farmers or has word spread

about a white man asking questions?

The statute of limitations does not

expire in murder cases, and I ask

him who shot Louis Allen. He shares

my suspicion of the sheriff. It is time

to go. Driving away I see a grandfather

talking with his grandson.

Jail, No Bail

At Parchman we’re stripped

and searched, issued a towel,

a bar of soap, a toothbrush,

sheets and pillow cases,

a striped prison outfit.

Filthy cells are full of bugs.

A jail is just another house,

less comfortable than most,

I admit, room service leaves

something to be desired,

if you like three squares

of rice and beans you can’t

complain, a mattress thick

as a poor man’s wallet

and twice as hard, no seat

on the toilet, rusty water

seeps from the tap, a view

through iron bars of a guy

in another cell staring back,

one visitor asked us to say

something in “commonist,”

entertainment is not out

of the question, cigarettes

smoked down to the filter

serve as chess pieces,

singing freedom songs

always lifts our spirits,

drives the guards crazy.

They took our sheets,

then our mattresses,

and when we wouldn’t

stop singing, our soap,

towels, and toothbrushes,

but we raise our voices,

“Keep your eyes on

the prize, hold on.”

Tales from Liberty

1

At a Frederick, Maryland, art gallery

I meet a bearded painter working in pastels

from Liberty, Mississippi. A sniper

in Laos—he tells of killing a man, a village

organizer, on his front porch—he might

have to take out one or two of his kids

but he gets his man on the first shot,

gives him three more to make sure.

Our special forces, he says, thought

nothing of hacking off a man’s head,

sticking it on a pole for the village to see,

of walking around with a girl’s pubic hair

fastened to a helmet. That’s how the game

is played, what’s hard to convey

is how exciting it all was.

2

When he says his last name my heart

jumps, and I ask about a relative

I suspect might have shot Louis Allen

in his driveway because he witnessed state

representative E. R. Hurst gun down Herbert Lee—

a local farmer helping Bob Moses register voters—

at a Liberty cotton gin.

“He was one mean piece of work,” he says,

“his kids was mean too, mean as snakes,

they’d as soon shoot you as look at you.”

The original ancestor, a thief in Scotland,

was smuggled here from Liverpool in a coffin.

The man I suspect was a police officer

in Alabama before he came to Liberty.

A died-in-the-wool racist he is part of

a hardcore group associated with a local

Baptist church. The murder of Louis Allen

is still unsolved.

3

Roland Sleeper, a conservative Black man

well-liked in Liberty, is in no way seen

as a trouble-maker, but every weekend

he gets drunk. The painter tells me

Sleeper is sitting on a wooden bench

before the courthouse and says something

to offend a white man.

They take him to

the Homochitto swamp, beat him so bad

he loses all his clothes. Then he goes

after the men who did it and hasn’t

been seen since. The town assumes

the swamp will keep its secrets.