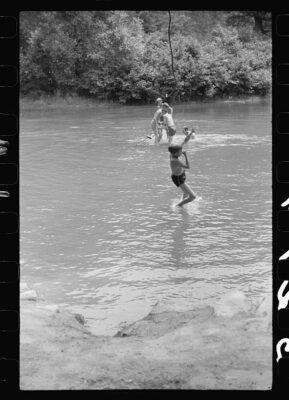

Southern Legitimacy Statement: I was born by coal oil lamplight in a tin-roofed farmhouse 6 miles outside Liberty, Mississippi. I list logging, plowing a mule, picking cotton and working in a country store in my resume. Learned to swim in an Amite River swimming hole–no lessons. My uncle went to school with Jerry Clower. My mother’s parents ran a dairy farm near Liberty. My Papaw Funderburk was State Overseer for the Mississippi Churches of God from 1935 to 1947. My cousin, Brother Caston, was sheriff in Liberty for many years. Another cousin, Carl Bates, from Liberty was President of the Southern Baptist Convention in the seventies. Graduated from LSU (“went in dumb and come out dumb too.”) Ssgt in USAFR 1965-1971. Retired parole officer.

Three Poems

Boys

In their mid-teens suffer from a mysterious and

Ubiquitous malady we’ll call, “Dramatic IQ Drop.”

We formed a car club in spite of the fact that the

Cajuns, whose steadfast qualifications were: inability

To smile; the central nervous system of a hammerhead

Shark; and an intense fondness for the sound and feel of

Knuckles colliding with human flesh, had forbidden

Any other clubs sporting their colors on campus.

At school: “We’ve got just as much right to wear club

Jackets as they do.” “Yeah. They can’t stop us.”

That night by phone: “You wearing your jacket

Tomorrow?” “Are you crazy? They’ll kill us.”

Everyone got the message but Floyd, quiet

and unassuming, who was appalled at our disloyalty.

A Cajun noticed the forbidden clothing, gathered his

administrative staff and headed our way. We disappeared

like rednecks from a BLM meeting, save for one. Looking back,

I saw a tight circle of bone, sinew and muscle clothed in

Cajun jackets.

KIA Minus One

Short-timer; Pungi stick survivor

Feces covered, piercing boot and foot

Infection held me 2 weeks. Limped some

In leaf-filtered dimness, a specter, black hair

Black pajamas; M-16 jammed; hurled it at the

Thin, startled face and charged before his

AK settled on my chest, my K-Bar finding

His heart; eyes wide and round and full of

Death. Only a boy, never made a sound

Three days left; walked past a Major, no salute

He attacked with unkind words. Told him, “I’m

Too short. Ain’t got time to be salutin’ no Major.”

Could hear him bellowing behind me all the way

To the chow hall. Grabbed some coffee, grinning

Hollow-faced buddies hiding envy with insults and

The sky blazed and thundered

Filled with the sound of jets

I hurtled from the earth

Darkness, deeper than a wound

Pain, flashing through a distant prism

Adrift beyond the windless stars

I became one with time

Zipped within a vinyl womb

I saw my father in the sun

Reaching toward me, his smile

Familiar and warm as breathing

Never feeling the femoral artery

Cut, giving back my life

With its faint, visible

Pulsing

As a Shadow

Again in the emergency room.

Wayne sat on a plastic chair,

head down, t-shirt ripped halfway

down the front, blood spattered,

left eye swollen shut, soon to

blossom with color. Will he ever

learn to keep his mouth shut?

Double doors banged open, but

the emergency no longer existed.

A white-suited attendant pushed

a gurney steadily and almost

silently across the lobby toward

a No Admittance sign. An arm

had fallen from underneath the

sheet, swaying slightly with that

unrestrained freedom that only

death can create. The arm was

smoothly and gracefully muscled,

without the bulk that would have

come later with manhood. Tattooed

on the outside of the bicep, the words

Born to Raise Hell eulogized a

brief and violent life.

Wayne turned his one-eyed gaze

toward the arm, his expression

never changing.

Maybe he’ll learn something from this.

“Remind you of anybody?”

He stared at the floor, nodding twice.

“Who?”

“My dad.”

The man in white pushed the body

of the boy on through the door

and down a dim hallway

toward the light

at the far end.