Southern Legitimacy Statement: When I was ten, eleven, twelve years old, I dreamed of moving up North to live in a garret and write novels–never knowing exactly what I’d write about, but it would be lofty. Fifty years later, I still live in the South, and I write about the heart and soul of what I know–people in Texas whose lives seem small and insignificant. Yet they are as important as the people up North.

Straw Man

The music machine faltered as it churned out “Turkey in the Straw.” On hot summer days, the straw man with his jutted jaw and slate hair wiped his brow and prepared to face children who gave him nickels for ice cream.

If a little dab would do most men, Blake Fritz pomaded his hair with extra dabs of Brylcreem. He slapped the sweat off his face and dispensed orange popsicles and Fudgesicles. He gave broken sticks for kids to glue together and transform into mountain cabins for history projects in 7th or 8th grade.

Sticky globs of melting orange, red, and brown, melted on sidewalk slabs, leaving behind indelible memories.

Thugs in a 1960s gang, the only one in town, roughed him up, ripped the sleeve of his white coat, and demanded, “Your money or your life.” He chose to give up his money and to find other paltry means for surviving.

He trudged mile after weary mile, sometimes swiping his clumps of hair, as he crossed the Brazos River bridge and headed toward the wings of his inward war.

As if asleep he sludged through a distant past where doctors refused to hear froth-gurgling lungs of men who could not breathe. Obscene cancerous scenes they brought back home, unsigned plaques with uninscribed slogans, remainders of the first “war to end all wars” where Wilfred Owen marched through bog after weary bog and prayed with iron-clad irony:

Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

In the second war of the worlds, army doctors diagnosed Blake with war neurosis, then PTSD. They shipped him home to cope and re-imagine vivid agonies night after harrowing night.

Back at home, 20 years later, he still trudged. His 40s model car, going defunct after his mother died—like the grandfather’s clock bought on the day of some young man’s birth, too big for the shelf, standing on the floor and succumbing at the same time as the man left this world to find his true home.

As he slogged through the snow, intermingling war scenes with home front casualties, he mumbled indistinct words. People said this was his way to remember stationary orders—but who knew what vague phrases from the vivid, haunted inner war he involuntarily summoned. He attended every service of East Side Church of Christ, praying Jesus who could heal all wounds would heal his.

For Townsend Realty and Insurance—he scribbled orders of office stationery with a gold embossed TRI and the name of Clark Townsend with his mailing address on the letterhead and on the envelopes.

The banker who served as the church accountant, once commented, “Time to file income tax in a couple of weeks.” And Blake, who never spoke unless someone else initiated a conversation, answered, “I don’t make enough to file.”

***

His brother Capt. Will Fritz filed other forms, took other notes, and wore other hats: an LBJ Resistol silver gray beaver fedora, too big for his face, but policemen ordered them as if in bulk. He passed his hats to Blake. By the time Blake got the weathered hat with all its pin-pricked dots, he had to crumple up the frayed self-conforming velvet lining.

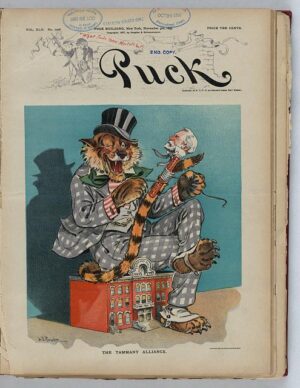

Crude, country, talking like a farmer, Capt. Will organized the homicide and robbery division of the Dallas Police Department. He conducted his own interrogations: “Boy, have you ever been a member of the Communist party?”

Old-time investigators took no notes since they could be misinterpreted by lawyers who knew but did not admit they knew this cardinal rule. He decided in advance the prisoner’s unspoken answer, which he already categorized in his mind as deception.

In one ten-year period, he had a 98% record for solving and convicting criminals. Even though Lee Harvey Oswald refused to confess, Capt. Will remained certain they had their man.

Then he received a call and commented, “The FBI has it now.”

He wrote hazy after-the-fact notes that blended into myth. A fellow detective once commented, “You used your own wits to convict culprits who could not tell the same story each time.”

Regardless, Capt. Will rounded up vagrants, and made sure they showered and ate at least this one square meal that day.

The isolated folktale remains: he drove through the night to see the only person he could trust. His brother Blake took possession of the notes and other details of that complex interrogation.